BONA, derived from the Zulu greeting to a multitude of people, 'Sanibona' - directly translated as 'we see you' - forms the premise of this publication, by Tebo Mpanza

my fellow lifeguards and I, Kagi & Thato after a solid shift by the pool

Christmas is layered. It’s packed with joy and nostalgia, presence and absence, celebration and reflection — all at once. It’s always been this way for me. Growing up in South Africa, Christmas was bright, loud, and hot. Now, it’s colder, quieter, and a little closer to what I once only saw in Home Alone. Kind of. Perhaps not entirely.

As a child, I spent most Christmases in Polokwane (Pietersburg at the time), where my father ran a water park business called Waterland. Every holiday, he was working, which meant no trips away for us. But for me, flying to Johannesburg, then a three-hour drive to Polokwane every December, was the holiday. I’d travel as an unaccompanied minor from Durban to Joburg — a small adventure I looked forward to every year.

I was probably a little older than this when my mom would send me off

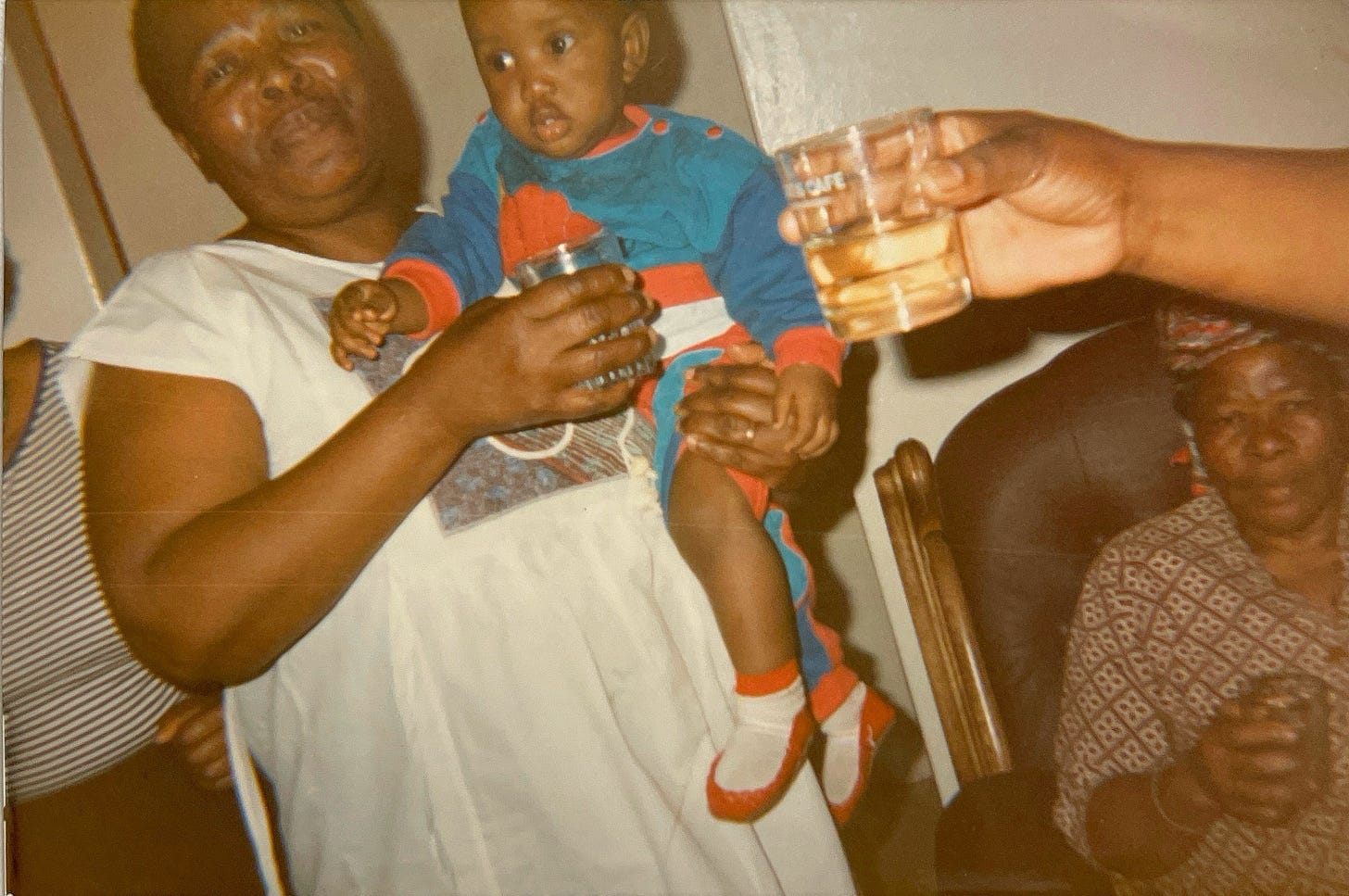

My grandmother on my dad’s side always made me feel like I was the most important grandchild. Every time I walked through the door, she embraced me like I was her favourite. I suspect she made all of us feel that way. She was a remarkable woman — a domestic worker who raised a teacher in my uncle Stan and a medical doctor in my father. I still don’t know how she managed it, especially in South Africa at the time.

Gogo (grandmother) carrying me, and her mother, my great-grandmother in the corner, wild (don’t worry about the drinks)

Waterland was ours — my half-brothers, cousins, and me. We ruled it. No limits, no rules, no schedule. We even appointed ourselves lifeguards, as 99% of the visitors didn’t know how to swim — bar the odd Afrikaans family. Those Christmases were carefree but carried their own weight. Looking back now, I can see the sacrifices dad made to give us opportunities we had. Still, some days were overshadowed by a sense of intrusion on my part, like I wasn’t quite the right fit.

Now, Christmas feels entirely different. It’s usually raining, the days are shorter, and we’re tucked into warm homes with festive lights. In those early days in England, my mom and I were living in Sheffield. Christmas was about community. It was just the two of us, so we gathered with other South African families to recreate the sense of home we’d left behind. Bring-and-share vibes. My favourite dish was Aunty Mpume’s lamb curry — no turkey in sight. The day would end with dancing to Tkzee and Mafikizolo. Those gatherings were joyful, but they also reminded me of who wasn’t there.

This year, I’m thinking about my son Maximilian’s first Christmas. I wonder what his memories will be. What traditions will we create for him? Will he think of Christmas fondly, or will he one day notice what’s missing — who’s missing — and wonder why? That’s the layer I feel most this year: the responsibility of shaping what Christmas will mean to him.

Christmas is a beautiful time, but it’s heavy for some too. It’s the weight of joy and longing, of presence and absence. It’s the collision of all the things we celebrate and all the things we remember. Maybe that’s why it feels so layered — it holds everything at once. But I’m learning not to avoid that weight. I’m learning to carry it, to embrace it, and to find the moments that matter in all its complexity.

Merry Christmas, ya filthy animals.

Beautiful